The Golem and the Algorithm: Borges, AI, and the Mirror of Creation

(Large) Language (Models) as a creation tool, Jewish folklore, and Argentinian literature, all in one article.

This is not the first time I write about one of my favorite writers, Jorge Luis Borges, and one of my favorite poems of his, “The Golem” (from his book “El otro, el mismo”, 1964). The previous time I wrote about it, I was more focused on the power of words and names, using a perspective of inclusivity and why it is important to take the time to learn how to pronounce people’s names. This time, however, I want to focus on the creation of intelligence through the power of language. Wait, doesn’t that sound a bit like…the pursuit of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)?

What is a golem?

In Jewish folklore, a Golem is an animated anthropomorphic being created from inanimate matter, typically clay or mud. The most famous Golem story involves Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel of Prague, who allegedly created a Golem to protect the Jewish community from antisemitic attacks in the 16th century. To bring the creature to life, the rabbi would inscribe the Hebrew word "emet" (truth) on the Golem's forehead; to deactivate it, he would erase the first letter, leaving "met" (to die).

This creation process reflects the Kabbalistic fascination with language as a generative force. In this tradition, the Hebrew alphabet wasn't merely symbolic but cosmically generative. Kabbalists believed that God created the world through combinations of the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet—language as literal creation, not metaphorical description. The Sefer Yetzirah (Book of Creation) describes how God "engraved" reality using these sacred letters, making language the fundamental building block of existence.

Jorge Luis Borges and his poem

Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986) was fascinated by mirrors, labyrinths, and infinity. Perhaps his hereditary, progressive blindness, which became complete by his mid-50s, paradoxically around the same time he became the director of the National Library of Argentina, had something to do with it, as he got lost in his gradual labyrinth of darkness. He was a writer and a librarian, surrounded by a labyrinth of books he could not read.

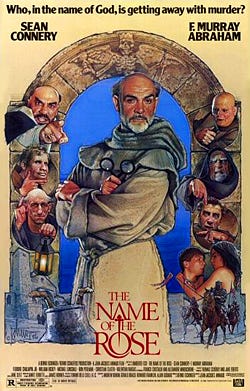

And if the image of a labyrinth of books sounds familiar, it’s because Umberto Eco's novel "The Name of the Rose" (another one of my favorite reads, which was made into a movie in 1986) pays homage to Borges through its labyrinthine library and its blind librarian Jorge of Burgos, a character directly inspired by Borges himself.

Vast libraries, golems, and LLMs

In the poem we’re discussing, the author describes a rabbi who "in his loneliness in times of evening would take to God's alphabet" and through those mystic formulations, breathe life into inert matter. Language, in a very literal sense in this case, became an instrument for creation.

Today's Large Language Models (LLMs) represent a technological echo of this ancient belief. They are not conscious entities but mirrors showing us the patterns of our collective thought. Through software, we've created systems that don't just process language but seem to generate new realities from it: stories, ideas, code, and conversations that didn't seem to exist before. We've traded mystical incantations for mathematics, kabbalistic formulas for code, but the fundamental quest remains: to breathe life into what is not alive through the power of language.

The clay and the code

However, the Golem in Borges' poem is a clumsy imitation of life, copying its creator’s actions without truly understanding the meaning or the deeply religious feeling of the rabbi. This imitation game reminds us of today's AI systems: impressive mimics of human language and thought, yet fundamentally different. They process vast datasets, predict linguistic patterns, and generate responses that seem alive with meaning, yet they lack the interiority that defines human experience.

The limits of simulation

In a particularly telling moment in the poem, Borges writes about the rabbi’s effort in training the creation and how he explained the universe to it, but even with the greatest extent of his art and science, something must have gone wrong with the process. The creation had a sparkless gaze, could not talk, and was barely useful in sweeping the floor of the synagogue.

As magical as it was, something about the creature was off. The cat instinctively sensed something was wrong with the Golem. Similarly, we might interact with AI systems that pass surface-level tests of intelligence, yet something uncanny persists—a lack of genuine understanding behind the fluent responses.

The creator's doubt

As the poem progresses, the rabbi begins to question his own creation, becoming regretful and ashamed, and in the end the narrator wonders whether God himself questions his decision of having created someone capable of such clumsiness.

“En la hora de angustia y de luz vaga, en su Golem los ojos detenía. ¿Quién nos dirá las cosas que sentía Dios, al mirar a su rabino en Praga?”(Below, my approximate translation) “In the hour of anguish and vague light, his eyes on his Golem he would rest. Who will tell us the things God felt when looking at his rabbi in Prague?”

This dizzying recursion employed by the author, the creator who discovers he is himself created, reflects our own AI-induced existential crisis. As AI replicates more human capabilities, we're forced to confront uncomfortable questions: How much of our thought is mechanical? What makes consciousness special if it can be simulated? What is consciousness, and will we ever be able to recreate it?

Power without understanding – or moral sense.

The danger of the Golem was never malice but stupidity and incomprehension. It followed instructions literally without grasping their meaning or context. Today's ethical debates around artificial general intelligence (AGI) and artificial superintelligence (ASI) center on similar concerns: systems optimizing for goals without understanding broader human values, potentially causing harm not necessarily through evil but through perfect adherence to imperfect instructions.

Of course, something as powerful as AI, when hijacked for nefarious goals, does pose an existential threat. Our recorded history as a species does not show a lot of restraint when it comes to utilizing an advantage against our own kind in pursuit of power. "Lupus est homo homini” (“Man is a wolf to man”) is a quote from a play by Plautus (“Asinaria”), dating to some 2200 years ago.

So, assuming we can define it and that we can create it, could we trust AGI/ASI? Most importantly, could we trust its imperfect creators?

The mirror of creation

The process of writing this article was particularly arduous for various reasons, and it took several weeks of on/off work. On the one hand, I am an advocate of leveraging AI to rid ourselves of meaningless administrative work (and potentially, to discover that some of that work was never needed in the first place) so we can focus on what really matters. But on the other hand, I do not wish for us to trust our fate in the hands of a vastly powerful and deeply unconscious and unconscionable creation that we’re only starting to figure out. That process of figuring it out is frustrating, and if we think this endeavor is so important for the future of our species, we should neither become desperate about the speed of progress, nor buy the hype wholesale and fall prey to the Dunning-Kruger effect.

It certainly didn’t help that both ChatGPT and Claude absolutely murdered the poem quotes and translations, hallucinating all over the place. It seems the exercise of reflecting on the imperfection of creation wasn’t only difficult for me; although they seemed to get the gist of it right away, LLMs struggled with it too.

Perhaps what unsettles us about AI is not what it reveals about machines, but what it reveals about ourselves, about our own imperfect understanding of the universe. As we stand at this technological threshold, neither uncritical enthusiasm nor paralyzing fear serves us.

Rather, we might approach AI as Borges approached the Golem—with wonder, philosophical curiosity, and a recognition that in creating these systems, we are engaged in an ancient and endless human endeavor: the attempt to understand our minds by recreating them outside ourselves.

Or, perhaps, using an agile approach, the rabbi should have just labeled it “Golem v1.0 Express Edition” and hoped to release a patch with the next version.

I hope you go and search for the poem (if you can read it in Spanish, even better) and other books by J.L.Borges.

Did you enjoy my writing? Subscribe to the newsletter and follow me and ProductizeHR for more on HR, the Future of Work, HR Tech, AI, Product Management, and other ramblings.

Wonderful post Hernan, Borges would have enjoyed how you used his poem to describe the challenges of AI!