A "Human in the Loop” Alone Is Not Enough

Human In The Loop (HITL) is a great step toward AI safety, but you need a lot more than just that.

TL;DR:

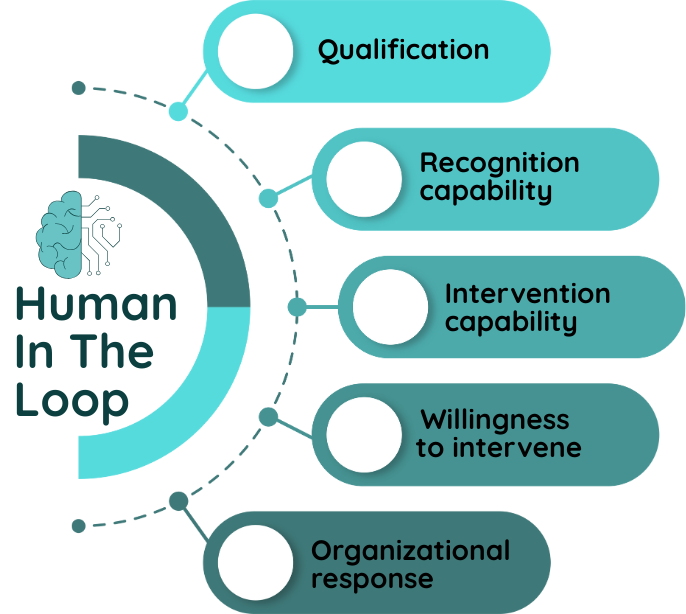

Most organizations treat “human in the loop” as a checkbox that provides AI safety, but real oversight requires five conditions: humans must be qualified to evaluate the decision domain, able to recognize AI failures (requiring knowledge and system transparency and reliability), able to intervene practically (not just theoretically), willing to act despite automation bias, and working in organizations that actually respond to their findings.

Boeing had qualified engineers catching problems; Tesla has drivers monitoring Autopilot; Amazon has managers who can override terminations. All had “humans in the loop.” All failed because having a human review AI decisions means nothing if they lack the expertise, capability, authority, psychology, or organizational support to actually prevent failures.

The “human in the loop” failed catastrophically, not because the humans failed, but because human oversight alone was never sufficient. If your organization is implementing AI systems and counting on “human in the loop” as your safety mechanism, make sure you’re not setting yourself up for the same failure pattern.

When HITL breaks down

In 2018, Boeing engineers Ed Pierson and Sam Salehpour warned company leadership about dangerous production conditions at their 737 MAX factory. He documented his concerns, escalated through proper channels, and requested the factory be shut down. His warnings were ignored. Less than a year later, two 737 MAX crashes killed 346 people.

Not only that: the US National Transportation Safety Board recently reported that the structural flaws that caused the crash of the MD-11F UPS plane in Kentucky in November 2025 had been identified by Boeing on similar planes back in 2011. Nearly 15 years earlier.

Boeing had humans in the loop. Quality engineers flagged defects, raised concerns, and documented problems. They knew how the systems broke, they had the authority to report issues, and they repeatedly tried to intervene. But the organization didn’t act. The “human in the loop” failed catastrophically, not because the humans failed, but because human oversight alone was never sufficient.

If your organization is implementing AI systems and counting on “human in the loop” as your lone safety mechanism, you’re likely setting yourself up for the same failure pattern.

The HITL Illusion

“Human in the loop” sounds like safety. It implies oversight, accountability, and a final check before something goes wrong. In practice, most HITL implementations are theater.

Organizations check the box—”we have human review of AI decisions”—without asking whether that human is actually qualified to evaluate the decisions, can catch problems, can stop them, or whether anyone will listen when they do.

The gap between HITL as concept and HITL as reality comes down to five questions. Your AI system doesn’t have real human oversight unless you can answer “yes” to all five.

Question 0: Are They Qualified?

Before anything else, does your human have the domain expertise to evaluate whether the AI’s decision is correct? This isn’t about understanding AI, it’s about understanding the decision itself.

Consider an AI system generating medical diagnostics. You assign a junior technician to review the outputs. Even with perfect transparency into how the AI works, this person lacks medical training to judge whether a diagnosis is accurate.

They can’t evaluate if the AI correctly identified a tumor, misread symptoms, or missed a critical indicator. They’re not qualified to review any medical diagnosis, AI-generated or not.

This happens constantly. Organizations assign HITL responsibility based on availability rather than expertise:

Non-technical managers reviewing AI code quality assessments

Entry-level employees reviewing AI-generated fraud detection

Content moderators reviewing posts in languages they don’t speak or cultural contexts they don’t understand

The Boeing example becomes even more striking here: they had qualified engineers with deep expertise, and the system still failed catastrophically. If qualified experts couldn’t make HITL work, what chance does an unqualified reviewer have?

Question 1: Can They Catch It?

Assuming your human is qualified, can they recognize when the AI makes a mistake? This requires understanding how the system fails and having transparency into why it made its decision. Most organizations fail here immediately.

Consider content moderation at scale: AI systems flag millions of posts daily, and human reviewers assess whether the flags are correct. But reviewers often can’t see how the algorithm works, what datasets trained it, or what pattern triggered the flag.

They’re evaluating “black boxes”—making judgment calls without the context needed to evaluate them properly.

The result: automated systems struggle to distinguish between posts condemning hate speech and posts promoting it. Human reviewers, lacking visibility into the AI’s reasoning, can’t catch these failures reliably.

False positives and faulty sensors can also be a problem. Here’s another example, this one again from the aeronautical industry: Austral Lineas Aéreas Flight 2553 (1997) and Air France Flight 447 (2009) (in)famously crashed due to faulty sensors: the pitot tube, which is used to determine airplane speed in flight, partially froze and didn’t report accurate speed readings, therefore the pilots made catastrophically wrong judgments, resulting in tragedy.

If your human can’t see the AI’s confidence scores, feature weights, or decision logic, and/or can’t trust the sensors, they’re not reviewing the decision, they’re guessing about it.

Question 2: Can They Stop It?

Even if your human catches a problem, can they actually intervene? This isn’t about permission on paper. It’s about whether the human has the practical ability to override the system given the time constraints, organizational pressures, and tool limitations they face.

Amazon’s warehouse productivity tracking offers a clear example. The company’s ADAPT system monitors worker performance and automatically generates termination notices without manager input. Managers can technically override these decisions, but Amazon doesn’t disclose how often this happens. The system is designed to operate autonomously—and internal documents show overrides are explicitly allowed during peak operations like Prime Day to protect business needs, but remain inflexible for worker circumstances.

When AI operates in milliseconds and humans have seconds to review, when overrides count against performance metrics, when the system is designed to minimize human intervention—the “ability to override” becomes theoretical rather than practical.

Question 3: Will They Try?

Assume your human is qualified, can recognize problems, and has the practical ability to intervene. Will they actually do it when the moment comes? Or will automation bias, overtrust, and learned helplessness prevent them from acting?

Tesla’s Autopilot provides the data here. Drivers are required to monitor the system and take control when needed. But research shows drivers became complacent over time, failing to monitor the system and engaging in dangerous behaviors like hands-free driving, mind wandering, or sleeping behind the wheel. NHTSA’s analysis of crashes found that in 82 percent of incidents, drivers either didn’t steer, or steered less than one second before impact, even when hazards would have been visible to an attentive driver. Internal emails revealed Tesla knew this was happening.

The incidents in airplanes with the pitot tube I mentioned in Question 1 may also have a component of this: since it is a well known fact that pitot tubes can accumulace ice buildup, they are equipped with equipment that heats up and melts the ice. But imagine that the light that indicates whether the heater is on malfunctions on rare occasions: a pilot might need to choose between trusting the light indicator or intuition. Too much confidence on “intuition and experience with malfunctions” and it can be a recipe for disaster.

After the AI makes 1,000 correct decisions, humans stop paying attention. They defer to the system, even when they shouldn’t. Your HITL process needs to account for this psychological reality, not pretend it doesn’t exist.

Question 4: Will It Matter?

This is where most organizations completely fail to think through their HITL design. Your human catches the problem, has the ability to intervene, and actually raises the concern. Now what? Does the organization act on the finding, or does the human’s intervention disappear into a void?

Boeing’s story illustrates this final failure mode most clearly. Multiple engineers caught safety problems and raised concerns through established channels. Sam Salehpour testified that “employees like me who speak up about defects are ignored, marginalized, threatened, sidelined and worse.” Ed Pierson’s warnings about manufacturing conditions were dismissed. The humans in the loop did everything right. The organization did nothing.

When findings are ignored, when psychological safety and trust are missing, when whistleblowers face retaliation, when concerns go unaddressed, humans learn to stop trying. Your HITL becomes rubber-stamping. The human knows that catching problems is futile, so they stop catching them.

What This Means for Leaders

If you’re implementing AI and planning to rely on human oversight, you need more than a human with override authority. You need to systematically build all five capabilities:

Qualification: Does your human have the domain expertise to evaluate this type of decision? Would they be qualified to make this judgment without AI? Are you assigning oversight based on expertise or convenience?

Recognition capability: Does your human understand how the system fails? Can they see the AI’s reasoning process? Do they have the domain expertise to spot problems? Is the system designed to be interpretable?

Intervention capability: Does your human have time to deliberate, or are they rubber-stamping under time pressure? Do they have tools to investigate edge cases? Can they override without career consequences? Is override authority real or theoretical?

Willingness to intervene: Have you designed against automation bias? Do you test for complacency? Are humans exposed to enough edge cases to maintain vigilance? Do your incentives reward catching problems?

Organizational response: When humans catch failures, does something actually change? Is there psychological safety to raise concerns? Do you have processes to act on findings? Is there accountability when HITL catches something?

Most organizations have none of these. They have someone with nominal authority to review AI decisions, no time or tools to do it properly, misaligned incentives, and no mechanism to act on their findings. That’s not human in the loop. That’s human in the blast radius.

A Final Question

Before you implement your next AI system with “human oversight” as the safety mechanism, ask yourself: if your human catches a serious problem tomorrow, do you know exactly what happens next? If the answer is anything other than “yes, and here’s the specific process,” you don’t have humans in the loop. You have a dangerous illusion of safety.

The question isn’t whether you have a human reviewing those AI decisions. The question is whether that human can actually prevent the failures you’re worried about. Most organizations are building systems where the answer is no—they just haven’t admitted it yet.

Did you enjoy the article? Like, comment, and share!

Also, follow me and ProductizeHR on LinkedIn for more articles.